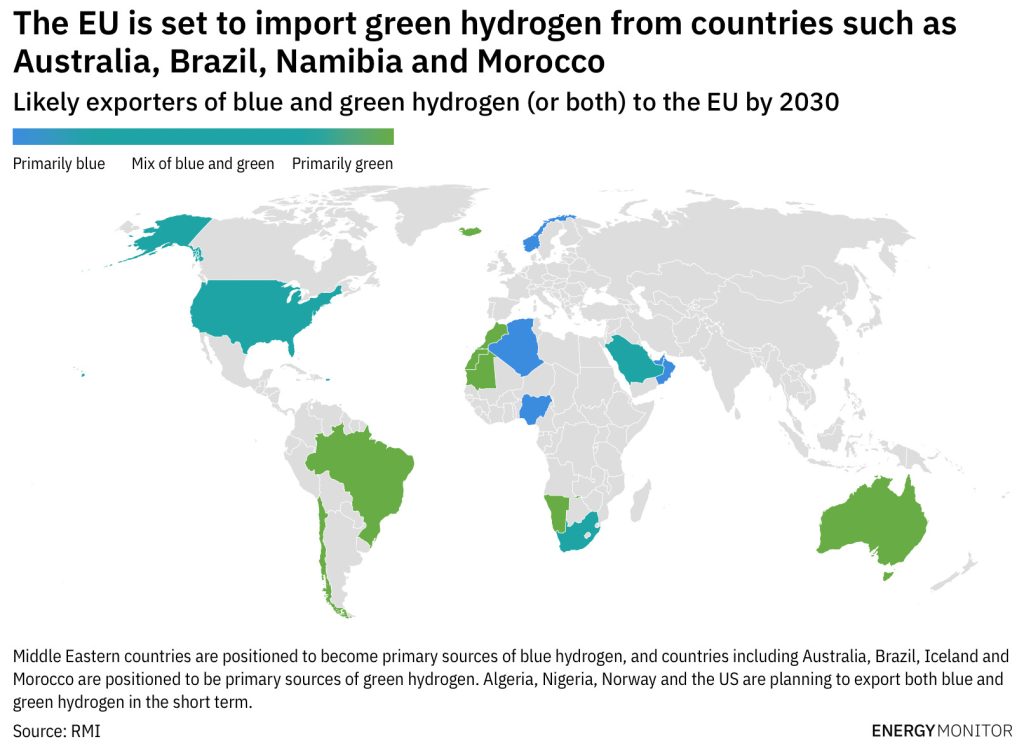

In 2021, the Namibian government went to Europe with plans to export three million tonnes per annum of green or renewable energy-produced hydrogen from an area in the south-west of the country as part of a post-Covid economic recovery programme. Germany, on the lookout for green hydrogen supplies, was quick to partner with its former colony. Namibia has an “excellent chance” of succeeding in the global competition for the best green hydrogen technologies and production sites, Federal Research Minister Anja Karliczek said in August 2021. She estimated Namibian green hydrogen could be the cheapest in the world, with costs falling to around €1.50–2.00 per kilogram (/kg).

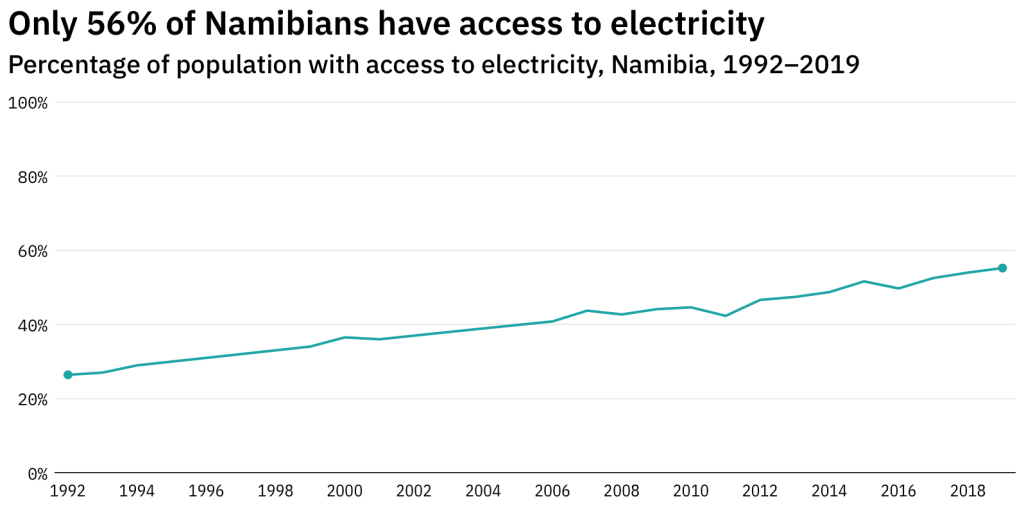

These are big claims for an industry still only in the pre-feasibility stage – and in a country that has never executed an infrastructure project of this size and complexity. Namibia does not generate enough electricity to meet its own limited demand – only 56% of the population has access to electricity – let alone support large-scale hydrogen production.

However, Namibia has the ingredients to become a renewable energy powerhouse, according to Marco Raffinetti, chief executive of Hyphen Hydrogen Energy, the company selected in November 2021 as the preferred bidder for Namibia’s first hydrogen project. “It has excellent co-located wind and solar resources, large swathes of uninhabited, government-owned land – and the industry has strong support from the government,” he told Energy Monitor.

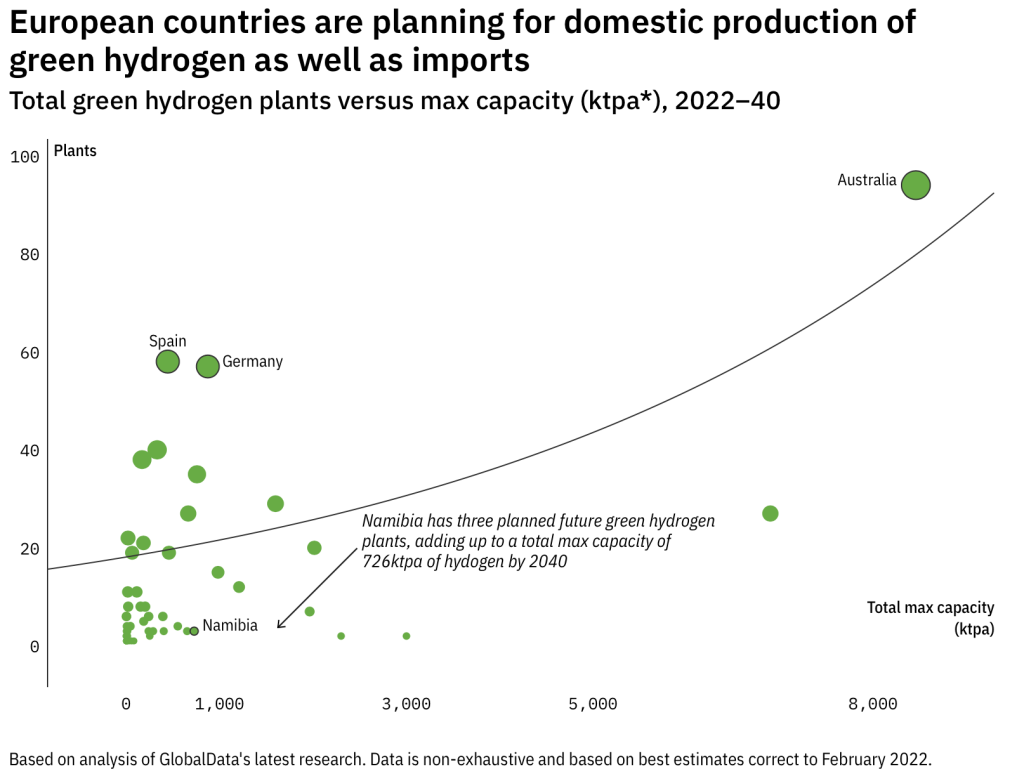

Hyphen – a joint venture between German renewable energy company Enertag and investment and project development company Nicholas Holdings – is working with the government on an implementation agreement that will trigger the start of a feasibility study for the project. The company plans to start production of the first 125,000 tonnes (t) of green hydrogen by the end of 2026. By 2030, it plans to be producing 300,000t of green hydrogen per annum using 5–6GW of renewable generation capacity and 3GW of electrolyser capacity.

Empowering African countries like Namibia to participate in the entire value chain of the green hydrogen economy could be transformative for the continent, says Amos Wemanya, a senior adviser at Power Shift Africa, a climate and energy think tank based in Nairobi – but the priority first needs to be on meeting each country’s basic energy and development needs. While Hyphen’s project may have the potential to improve local access to energy, this needs to be cemented into its development plans.

“We need to set standards to hold the various participants in the green hydrogen economy accountable and that apply not only to the Namibian government but also investors, and investing countries, like Germany and the EU,” he says. Power Shift Africa put forward suggestions for these standards in a green hydrogen position paper published in January 2022 with civil society organisation Germanwatch. Chief among them is the guarantee that the water and energy used in projects are additional, and not drawing on existing local supplies.

The Hyphen project will use desalinated water for its plant, a process that Raffinetti says will only add a couple of cents per kilogram to the final delivery price of Namibia’s hydrogen.

The water requirement is “pretty small”, he says, with 1kg of hydrogen only requiring around 9kg of water.

However, the issue with hydrogen production is not water use, it is energy use, says Martin. “Pure water electrolysis requires about 50–65kWh of electricity per kilogram of hydrogen produced,” he explains. “Producing enough freshwater by desalination of seawater to make 1kg of hydrogen takes about 0.035kWh by reverse osmosis.”

The electricity that goes into the production of just 1kg of electrolytic hydrogen could instead make around 14,000 litres of pure water for Namibians to use, he says.

A big opportunity – a big risk

The green hydrogen industry is in its infancy, and it is difficult to predict how the market will develop in the long term. Depending on global climate ambitions, sector-specific activities, energy efficiency measures, direct electrification and the use of carbon capture technologies, hydrogen demand by 2050 could vary from 150 to 500 million metric tonnes per year, according to a report by the World Energy Council and PwC.

Hydrogen is an expensive bet for Namibia. Hyphen estimates its project will cost around $10bn (N$159.9bn) – roughly the equivalent of Namibia’s annual GDP. The Namibian government could take up to a 24% stake in this, raising up to $500m for its own equity, Mnyupe told Bloomberg at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, in May 2022.

The Hyphen project has already attracted the interest of some lenders, particularly development finance institutions. “There is strong appetite to see projects of this nature succeed on the African continent, and in Namibia specifically,” says Raffinetti.

However, there are questions over whether this is a misuse of climate finance, which should be focused on local development, rather than export projects. “This is about trade and investment deals for European green targets, a complete distortion of what clean development is supposed to look like,” says Pascoe Sabido, a researcher and campaigner at Corporate Europe Observatory, a non-profit.

If the European market does not develop at the speed and scale the industry hopes, Namibia will be left “with a very large debt that its own population will have to pay”, says Sabido. “European companies – subsidised by the EU – are going to do very well out of this, but I don’t think Namibians are,” he says.

Ultimately, too little is understood about all the complexities of the green hydrogen import industry, researchers at the Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research concluded in a 2020 report: “The challenges and tasks to be solved in the future are therefore partially underestimated,“ they warned. Green hydrogen development could present a great opportunity for Namibia and a catalyst for renewable energy investment, says Kerstin Opfer, a policy adviser at Germanwatch. “But only if it is done right,” she adds. “The first priority needs to be ending energy poverty and creating access; the second, accelerating renewable energy deployment; and the third, maximising energy efficiency. Only then, perhaps, green hydrogen can also come into play.”

Source article: Energy Monitor